Hey there 👋!

With multicore processors now standard, it’s essential for high-performance applications to harness this power through effective concurrency. Java’s Fork/Join framework, part of the java.util.concurrent package since JDK 7, optimizes the efficiency of multi-threaded tasks, fully utilizing the capabilities of modern hardware. In this article, I’m going to delve into the Fork/Join framework, explaining its purpose, significance, and application, all illustrated with a practical example.

What the fork?

The Fork/Join framework is an implementation of the ExecutorService interface that helps developers solve problems using divide-and-conquer algorithms. These algorithms work by breaking down a task into smaller, more manageable pieces, solving each piece separately, and then combining the results. In this framework, any task can be forked (split) into smaller tasks, and the results can be joined subsequently, hence the name “Fork/Join.”

You may wonder, “Why opt for the Fork/Join Framework when traditional threading is an option?”

Hmm, why?

Picture multitasking. But it’s Java juggling your tasks with finesse! Aaaaand it’s all about efficiency, and here’s why: -

- Efficient Thread Utilization: It makes use of a work-stealing algorithm, where idle threads “steal” tasks from busy threads’ queues. This ensures that all threads are actively used, reducing overhead and improving performance.

- Handling Recursive Tasks: The framework excels at handling recursive computations, a common scenario in divide-and-conquer algorithms.

- Improved Scalability: It’s designed to scale well to available parallelism, which means better performance on multicore processors.

How does it work?

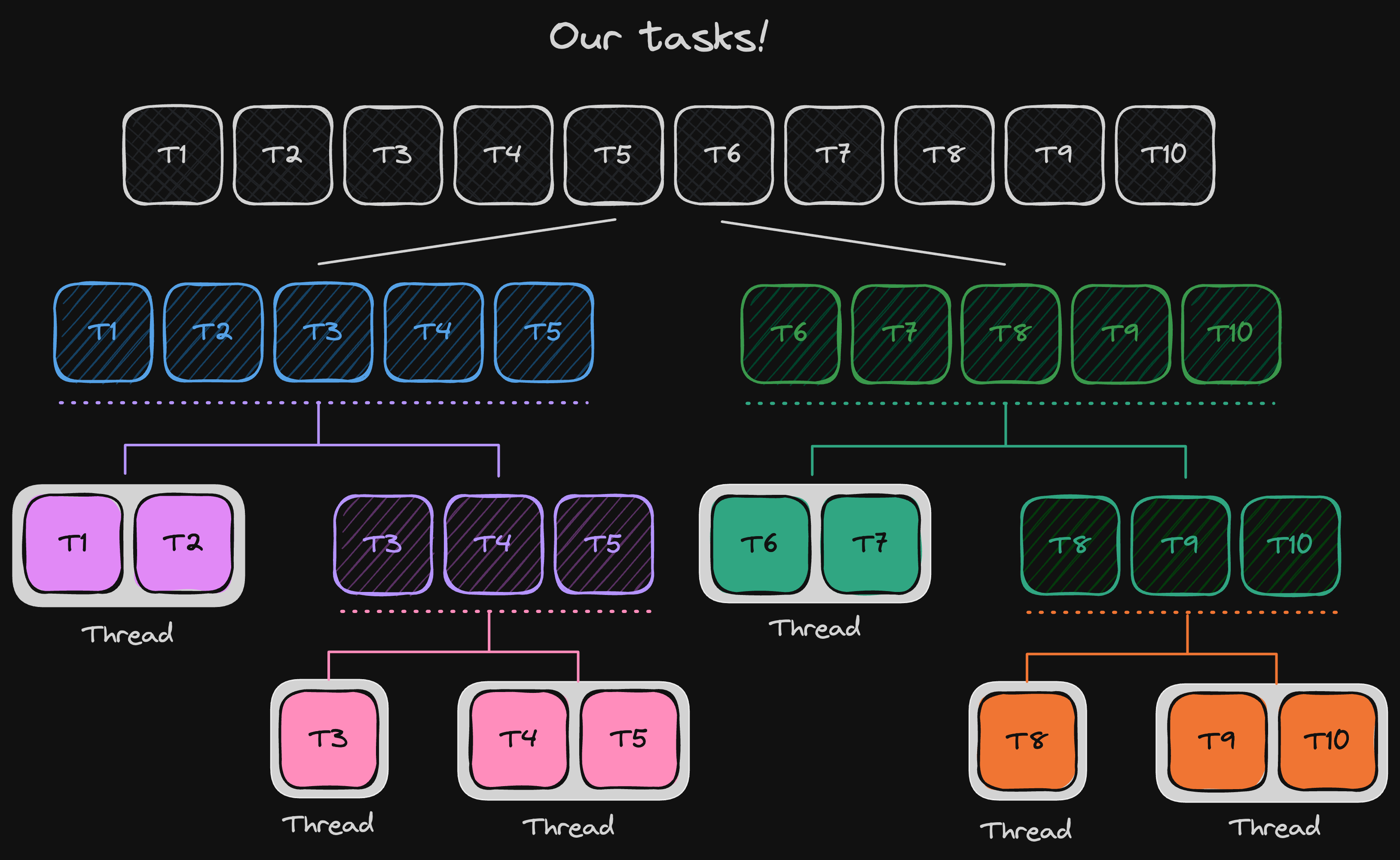

Consider a scenario where you’re faced with an array of 10 tasks, each representing operations that are resource-intensive, such as database or I/O operations.

Your objective is to expedite the processing of these tasks efficiently without overburdening the system resources. Sequential execution is off the table due to time constraints, and a single thread can handle a maximum of two tasks consecutively. Intriguing challenge, isn’t it? Let’s tackle this problem by employing a divide-and-conquer strategy.

As demonstrated, our goal is to systematically divide tasks until they’re manageable enough, aligning with our defined threshold. Wondering how this translates into Java? Stay with me; it’s simpler than it seems.

First, let’s establish our base scenario. Imagine a Task class, responsible for handling time and resource-intensive operations—think bulk updates, I/O, network calls, and more. Here’s a glimpse of what it looks like:

public class Task {

private final int id;

// Other necessary fields...

public Task(int id) {

this.id = id;

}

public void process() {

// Note: exception handling omitted for brevity

System.out.printf("Processing task %d...%n", id);

Thread.sleep(TimeUnit.SECONDS.toMillis(3));

}

}

However, we can enhance our approach by abstracting the process() method, leading us to define a Computable functional interface and implement it in our Task class, like so:

@FunctionalInterface

public interface Computable {

void process();

}

public class Task implements Computable {

// Existing code...

}Noice 😎! That’s so much neater, isn’t it? Next, we generate an array of random tasks, shifting our focus to the crux of the issue: parallel execution.

private Task[] generateTasks(int count) {

Task[] tasks = new Task[count];

for (int i = 0; i < tasks.length; i++) {

tasks[i] = new Task(i + 1);

}

return tasks;

}But how do we execute these tasks in parallel? Enter Java’s Fork/Join framework. Here’s a simplified guide:

- Extend

RecursiveTask<R>orRecursiveAction, depending on whether you need a result. - Override the

compute()method to specify the task’s logic and the conditions for further splitting or direct execution. - Engage a

ForkJoinPoolto invoke the root task.

Let’s start with step 1, creating a class named TaskProcessor extending RecursiveAction, and override the compute() method:

import java.util.concurrent.RecursiveAction;

public class TaskProcessor extends RecursiveAction {

// We do our initialization here...

@Override

protected void compute() {

// Task execution logic...

}

}In step 2, we refine our TaskProcessor to accept an array of tasks and employ a loop within compute() to handle tasks sequentially. But there’s a catch: we haven’t set the base condition for task division. Here’s where start and end come into play, marking the range of tasks processed by each TaskProcessor instance. This range helps us determine when to divide tasks further or process them directly, based on a THRESHOLD.

public class TaskProcessor extends RecursiveAction {

private static final int THRESHOLD = 2; // This can vary

private final Computable[] tasks;

private final int start;

private final int end;

public TaskProcessor(Computable[] tasks, int start, int end) {

this.tasks = tasks;

this.start = start;

this.end = end;

}

@Override

protected void compute() {

if (end - start <= THRESHOLD) {

for (int i = start; i < end; i++) {

tasks[i].process();

}

} else {

int middle = start + (end - start) / 2;

TaskProcessor leftProcessor = new TaskProcessor(tasks, start, middle);

TaskProcessor rightProcessor = new TaskProcessor(tasks, middle, end);

ForkJoinTask.invokeAll(leftProcessor, rightProcessor);

}

}

}The middle calculation (start + (end - start) / 2) ensures a consistent split of tasks1, with leftProcessor and rightProcessor handling each segment. The call to ForkJoinTask.invokeAll() initiates parallel execution. After setting up our tasks and creating the TaskProcessor class, we need to instantiate a ForkJoinPool and start our tasks.

Here’s how we can do it:

import dev.yasint.labs.forkjoin.Task;

import dev.yasint.labs.forkjoin.TaskProcessor;

import org.junit.jupiter.api.Test;

import java.util.concurrent.ForkJoinPool;

public class ForkJoinTest {

@Test

public void forkJoin() {

final Task[] tasks = generateTasks(10);

TaskProcessor taskProcessor = new TaskProcessor(tasks, 0, tasks.length);

ForkJoinPool pool = ForkJoinPool.commonPool();

pool.invoke(taskProcessor);

pool.shutdown();

}

private Task[] generateTasks(int count) {

Task[] tasks = new Task[count];

for (int i = 0; i < tasks.length; i++) {

tasks[i] = new Task(i + 1);

}

return tasks;

}

}And just like that, it works! Super quick and almost like magic. Your tasks are done before you know it! So, it works super-fast, but how, huh? Let’s take a simple look at the main code that makes this happen:

- We first generate our tasks using the

generateTasks(10)method, which returns an array of ten Task objects. - We create an instance of

TaskProcessor, passing the tasks along with thestartandendindices. - We then instantiate the

ForkJoinPool. We can either useForkJoinPool.commonPool(), which reuses the common pool shared among all ForkJoinTasks, or create a new instance with a specific number of threads usingnew ForkJoinPool(numberOfThreads).

Pool Selection?

The common pool is generally recommended unless you have specific reasons for wanting to separate the tasks from the common pool (like different thread settings, priority, etc.).

- Then, we initiate the task with

pool.invoke(taskProcessor). This starts the process, invoking thecompute()method ofTaskProcessor. Theinvoke()method is synchronous—it blocks until the task is complete. - Finally, it’s a best practice to shut down the pool after all tasks are complete using

pool.shutdown(), especially if you created a new instance of ForkJoinPool. Not shutting it down can lead to resource leaks.

Moving from best practices to performance considerations, it’s essential to evaluate the efficiency of our implementation. Analyzing the runtime complexity, the algorithm gives us a time complexity of , given the recursive halving of tasks and the processing time for tasks.

Conclusion

The ForkJoinPool handles the heavy lifting of worker thread management, task synchronization, and other low-level details. The invoke() method of the pool executes the specified task and any subtasks that it may create, utilizing the available threads in the pool.

The framework ensures balanced distribution of tasks among threads and efficient execution, leveraging the divide-and-conquer principle we implemented in the compute() method of our TaskProcessor.

I hope this guide made Java’s Fork/Join framework easier for you! Thanks for sticking around 🥰.

Footnotes

-

Consistent split of tasks: The divisor for

middletypically is2, dividing the task list in half, but it can be adjusted depending on how you want to split tasks.int oneThird = start + (end - start) / 3; int twoThirds = start + 2 * (end - start) / 3; TaskProcessor firstThird = new TaskProcessor(tasks, start, oneThird); TaskProcessor secondThird = new TaskProcessor(tasks, oneThird, twoThirds); TaskProcessor finalThird = new TaskProcessor(tasks, twoThirds, end); invokeAll(firstThird, secondThird, finalThird); // Fork new subtasksAbove is a hypothetical example if you were to split the task into three subtasks instead of two. ↩